Electric fusion AZS (Alumina-Zirconia-Silica) refractory materials are cornerstone components in modern glass furnaces, critical for maintaining integrity under severe thermal cycles. One persistent challenge is managing the alkali metal oxides content — primarily sodium oxide (Na2O) and potassium oxide (K2O) — known to compromise glass phase stability and reduce resistance to thermal shock. Drawing upon over thirty years of production expertise, this article demystifies the manufacturing process steps that significantly lower these oxides, thereby strengthening the refractory’s performance.

The foundation of low alkali oxide content lies in sourcing ultra-high purity raw materials. Typical industrial AZS batches contain alumina (Al2O3), zirconia (ZrO2), and silica (SiO2) with impurity levels tightly controlled to under 0.01% for alkali oxides. Advanced suppliers employ pre-treatment and refining to minimize trace contaminants. Scientific proportioning—commonly 45% alumina, 35% zirconia, and 20% silica by weight—also plays a pivotal role. Precise stoichiometric balance ensures glass phases form with minimal free alkalis.

Fusion takes place in an electric arc furnace capable of reaching temperatures around 1850–1950°C. Maintaining strict thermal stability is essential to promoting complete vitrification while allowing undesirable oxides to volatilize or integrate into stable compounds. Real-time temperature monitoring combined with controlled electrode positioning optimizes melting duration, limiting alkali segregation. Empirical data suggests that extending holding time by 20% at peak temperature reduces Na2O content in the melt by up to 30%, significantly improving final properties.

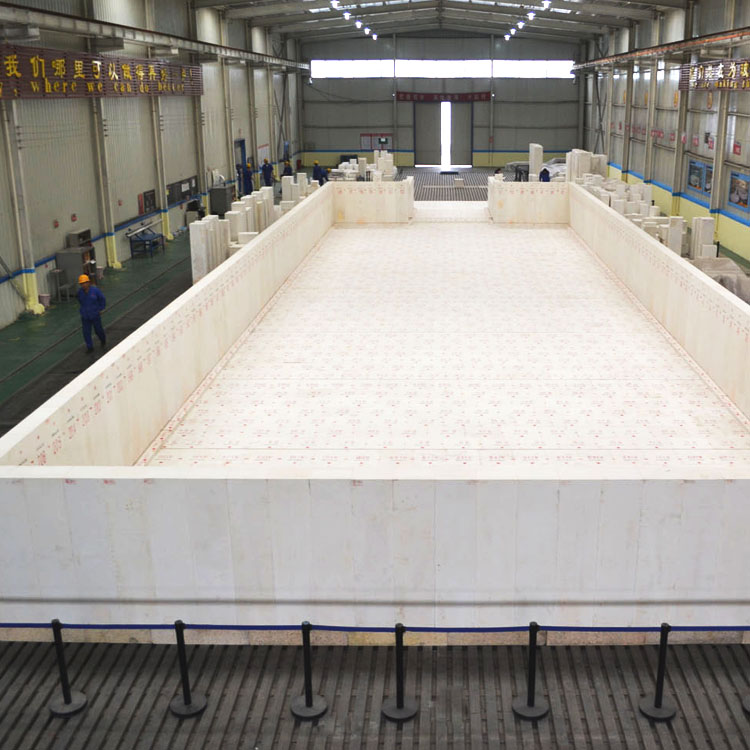

Following fusion, the homogeneous molten AZS glass is poured into preheated molds under inert atmospheres to prevent oxidation fluctuations. The temperature gradient during solidification critically affects the crystalline glass phase microstructure and alkali distribution. Controlled cooling at a rate of approximately 2–5°C per minute ensures even crystallization, reducing internal stresses and alkali mobility. Process engineers have documented that implementing a stepped cooling curve with holding plateaus around 1250°C yields a 15–25% increase in thermal shock resistance.

The key chemical mechanism involves volatilization and incorporation of alkali oxides into more stable spinel and zirconia phases during high-temperature fusion. This reduces free alkali content in the residual glass. Oxygen partial pressure and furnace atmosphere composition are crucial for promoting these reactions. Practical experience shows that adjusting oxygen input by 5–10% during melting decreases alkali oxide content from typical 0.20% ranges down to sub-0.10%, thereby enhancing material stability.

In real-world applications, temperature swings and atmospherical changes in glass furnaces pose risks to refractory integrity. Incorporating buffer layers and applying optimized post-fabrication heat treatment cycles can compensate for minor alkali oxide variations. Data from long-term industrial trials reveals treated AZS bricks maintain thermal shock resistance 20% higher than untreated counterparts over 24 months of operation. Preventive maintenance protocols aligned with these findings contribute to significantly reducing unplanned downtimes.